Geology & Landforms

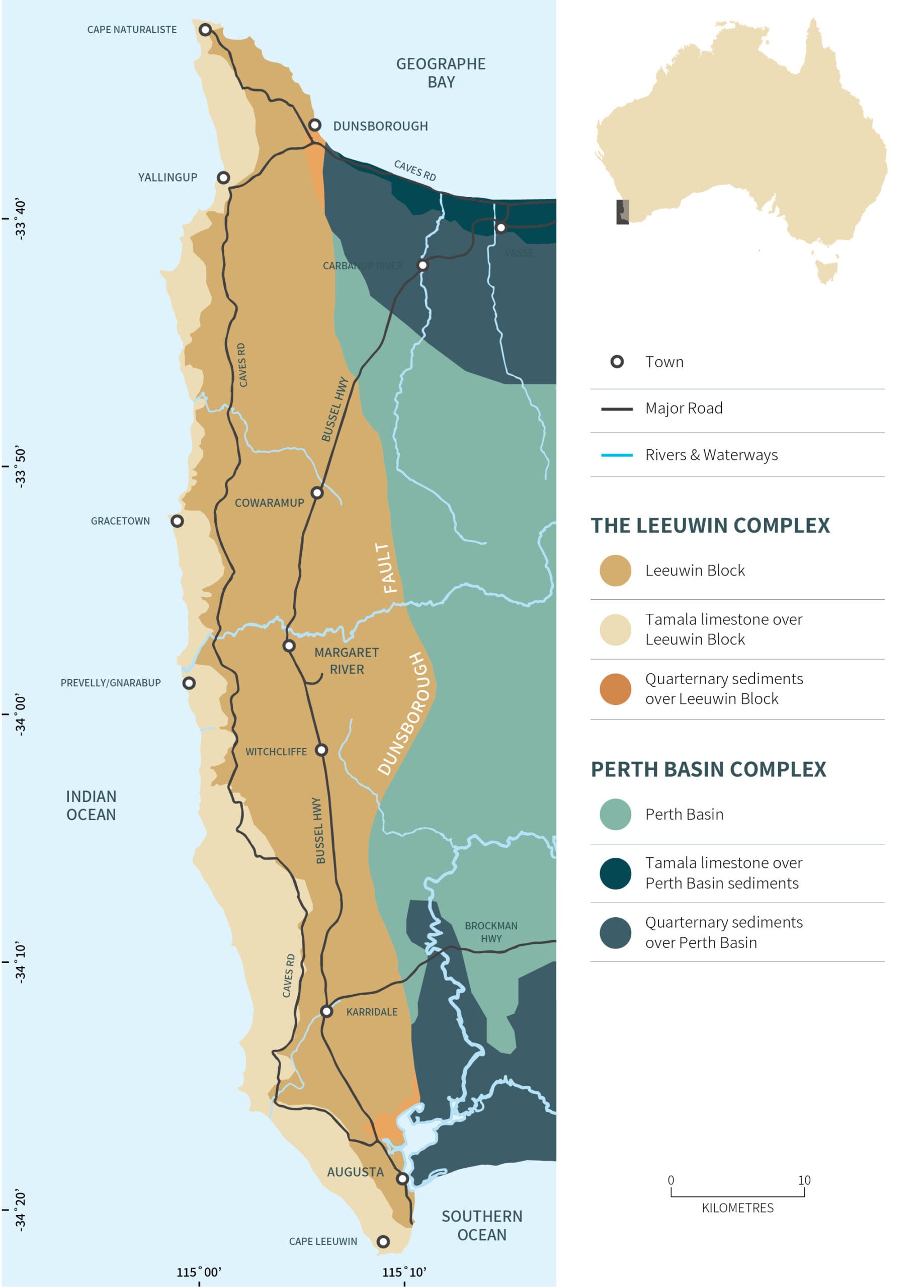

The Margaret River Wine Region is characterised by its distinct shape, which deviates out from the main coastal line with capes at its north (Cape Naturaliste) and south (Cape Leeuwin), as well as its diversity of landforms.

The Margaret River Wine region covers 213,000 hectares of land, running 110 kilometres north to south, and 27 kilometres west to east.

The land is defined by two unique areas split by the Dunsborough Faultline, which runs the full length of the region, vertically. To its west, the Leeuwin Complex, with its laterite foundations, high elevations, streams and valleys, is the prized land for over two-thirds of the region’s vineyards. To the east, are sandy soils formed by the decomposition of sedimentary rock.

The diverse landforms across the region support an array of viticulture options and wine styles. 46 percent is cloaked in remnant vegetation, including Jarrah (Eucalyptus marginata), Marri (Corymbia calophylla) and Karri trees (Eucalyptus diversicolor).

Margaret River’s Uniqueness

VITICULTURE LAND

3% of region

5,840 hectares

GEOLOGY AGE

1,130 & 1,600 million years

GEOLOGY TYPE

Gneiss & granite rock

ELEVATION

0-231 metres

(vines 3-140m)

Land of the Saltwater People

The Margaret River Wine Region is located upon the ancient lands of the Wadandi People, the traditional owners, who have lived in harmony with the environment of Wadandi Boodja (Saltwater People’s Country) for over 50,000 years. The Wadandi people are deeply connected to the natural resources of the land and sea and utilise these according to a cultural lore (learning and knowledge of tradition) to look after country. The maintenance of biodiversity has always been linked to the health of Wadandi people, both spiritually and physically.

There is a significant spiritual connection to the spectacular cave systems that lay beneath the surface along the length of the Leeuwin-Naturaliste Ridge, where ceremonial sites, rock art, paintings and artefacts are preserved. Cultural sites of significance also include the Nannup Caves, Jewel Cave, Devil’s Lair and a Birthing Lake. The Devil’s Lair Cave in Margaret River has provided evidence of some of the oldest records of human occupation in Australia.

The Wadandi seasonal calendar includes six different seasons in a yearly cycle. Each represents the seasonal changes of prevailing weather and with associated growth and activities of flora and fauna. The six seasons are Birak, Bunuru, Djeran, Makuru, Djilba and Kambarang.

The geology of the Margaret River Wine Region is dated as perhaps the oldest of the Earth’s viticultural regions, surpassing South Africa and Europe, with its granite and gneiss rocks aged between 1,130 and 1,600 million years old.

The Soils of Margaret River Wine Region

One of the most distinguishing features of the soils of Margaret River is the extent of change that occurs across the region and how frequently they can transition, even across a single block of vines. In many vineyards, the soil profile can alter significantly within a matter of metres. This landscape allows vignerons to match grape varieties by row and produce an array of wine styles over small land areas.

Since the earliest days of viticulture in the region, the specific preference towards land cloaked in the Jarrah, Marri and Karri trees (Eucalyptus marginata, Corymbia calophylla and Eucalyptus diversicolor) has guided vignerons as to what lies under the surface of adjacent paddocks, many of which were cleared by farmers before the wine industry.

Forest Grove (ironstone gravels) make up the highest percentage of vineyard area at 45 percent, and Mungite (sandy duplex) soils are next, at 29 percent. Ten main soil type groupings have been identified.

“These ironstone gravels are of pedogenic origin, that is, they have formed within the soil. This is a strong point of difference with other regions, particularly those in Europe, where gravelly soils comprise fragments of quartz, quartzite, limestone, basalt, flint and other rocks.”

Peter Tille & Angela Stuart-Street Soil Scientists